Digital Pitch Shifting: Early work

One of the first discussions of time-domain digital pitch shifting can be found in a paper from a 1972 Audio Engineering Society convention:

Time Compression and Expansion of Speech by the Sampling Method

In this article, Francis F. Lee describes using digital storage to perform the same pitch shifting and time compression techniques that the older rotary tape head devices were used for. A fair chunk of the article is dedicated to the relative virtues of the bucket brigade technique versus random access memory, but I just skimmed over that, as neither of the techniques described apply to modern digital systems. The older digital boxes would change the actual output sampling rate in order to perform pitch shifting, as opposed to the interpolated reads at a fixed sampling rate that modern digital systems use.

An interesting part of the article is when Lee describes the artifacts caused by splicing together the shifted chunks of audio. If the chunks are simply switched in between, the result is very obvious “clicks” in the sound. From the perspective of a DSP developer 38 years later, I would compare this to using a single sawtooth oscillator to modulate a delay line. This results in a pitch shifted signal, but with some nasty clicks at the frequency of the sawtooth, as the delay length abruptly changes when the sawtooth resets.

Lee explains how the older rotary tape head devices could be adjusted to reduce such artifacts:

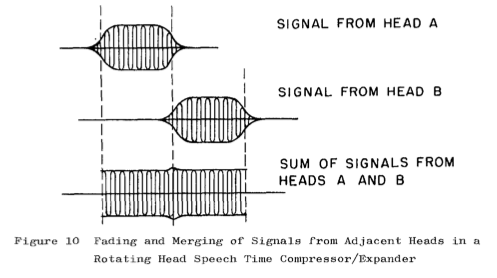

With the rotating head machines, by making the tape wrap-angle slightly more than the nominal 90 degrees, it is possible to have signals picked-up by adjacent heads to have a degree of overlap. Furthermore, as the tape and head come into contact or separate, the picked-up signal does not come up or drop off abruptly. The no-signal or signal to no-signal transitions are faded in and out, although rapidly.

An excellent illustration of this idea is included:

This is in sync with a process Wendy Carlos describes in her blog post on the Eltro Information Rate Changer, for adjusting the tape guides on the rotary head apparatus:

This is in sync with a process Wendy Carlos describes in her blog post on the Eltro Information Rate Changer, for adjusting the tape guides on the rotary head apparatus:

[The tape guides]were drilled off-centered to their support screws. So you could loosen the guides with an Allen’s wrench, and swivel them slightly. That way the nominal 90 degree angle the tape wrapped around the head drum could be increased or decreased, for best sounding results. A greater angle gave more of an overlap as one gap pulled away and the next one came in contact, and vice versa. You eventually learned where the optimum settings were for different material: speech, music, sound effects.

As we will see, the efforts taken to adjust the overlap between segments and minimize the glitches that result when combining segments are critical for obtaining a good sound with pitch shifted feedback, as used by Eno/Lanois.

Comments (1)

Comments are closed.